Welcome to the cKotch.Com blog. I’m Christopher Kotcher, and this is how a worthy difficulty helped me grow.

A Goal Unmet

I wanted a 4.0 GPA in college. At every orientation meeting, I proudly declared this desire.

I likely could have met my goal. Instead, I joined the campus’s Honors Program.

The Honors Program at University of Michigan-Dearborn contained challenging courses rooted in classical discussion-based learning. The program’s catchphrase was “Imagine Sisyphus Happy.” Sisyphus, the Greek figure forever condemned to roll a boulder up a hill in the underworld. We were to accept the program’s “worthy difficulty” and be happy with the labor.

Eight courses formed the Honors Program: two composition courses, an overview of Western Civilization, four history classes, and one tutorial course. The tutorial topics rotated every semester.

The program also stressed writing as the way to develop thinking. This is what pulled me in the most. Writing is a big part of my life . I was convinced I had a natural talent, and I wanted a chance to prove it.

My group interview to enter the Honors Program only convinced me more of my abilities. The discussion felt like a typical day in my high school AP World Literature class. Talking points spanned from Ancient Greece to the modern day. Instructors played devil’s advocate to controversial ideas to try sparking reactions.

Honestly, I felt more joy getting my acceptance for the Honors Program than my acceptance letter for the university.

That feeling would certainly shift after my first semester.

The First Few Classes

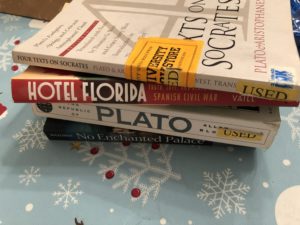

My first two honors courses were Honors Composition and the Four Trials.

Honors Composition started slowly. We read short essays and did brief writing exercises.

Four Trials was the overview course of Western Civilization. It focused on four figures from across Western history who had been put on trial for ideas deemed dangerous.

Discussions were awesome in these first two honors courses. Only a few select freshmen were in the Honors Program. We were a pretty tight-knit group.

I eagerly awaited these classes’ first essays. I wanted to prove myself.

Eventually the time came. Honors Composition asked me to discuss a personal difficulty, and Four Trials wanted me to analyze the trial of the philosopher Socrates in ancient Athens.

I threw myself into these essays. They were nothing less than my best effort. I even turned them in with a wide grin on my face. I could not wait to get them back and see how well I did. When the day came, I could not believe the results.

My composition essay received a B-, and my Four Trials essay earned a B.

Hard Work Saves the Day?

Now I know these grades are nothing to worry over.

But at the time? I felt horrible.

I had been ranked third in my high school class. On Facebook, my high school friends were posting incredible grades and comments on their first college assignments.

It was a real spirit crusher to start low in hard classes that would only get harder.

My sense of pride as a writer was shot for a few days too.

That part is especially silly looking back. I was mainly a creative writer, and those essays were all about analysis. They were about looking at the smaller parts of how great works work. Not about making my own great work.

Still, this was the first time something I had written did not seem to meet expectations.

After some moping, I took a breath and ran some calculations. I set goals for my future essays so I could recover from my past failings. I combed through my professors’ comments to try decoding their expectations.

In Honors Composition, the grade rose on each new essay. Quiz grades and rewrites further helped me finish the class with an A.

Four Trials though, that was a roller coaster.

My second essay dropped to a B-. I did not know how to improve. So, I wrote my third essay like my first one and accepted my B. Even after rewrites, discussions, and the final essay, I could only raise my final grade to a B+.

My chance at a 4.0 was virtually gone.

I considered dropping the Honors Program. But I finally decided to keep going. The discussions were still engaging at the very least, and I had some good friends in the program. Plus, I was excited about my professor for the program’s first main history course.

The Program’s Best Professor

Professor R (a nickname only on this blog) got in your face during lectures. He left overly detailed charts and drawings on chalkboards that seemed absolutely senseless to all but his students.

Obviously, he was one of my best college professors.

The class’s focus was the Greeks, specifically Socrates, his student Plato, the epic poet Homer, and some playwrights. Essentially, the course was an extended version of the Four Trials’ first unit.

Every class session was a sight to see. The class-wide favorite had to have been R’s lecture on Plato’s Metaphor of the Cave.

The Metaphor of the Cave asserts people prefer to bind themselves to illusions and images rather than reality. They essentially live chained in a cave where they see nothing more than shadow puppets. Philosophers are those who escape the cave into the light of the true world. Seeing this light leads them to return to the cave. They now wish to guide the other cave dwellers outside.

This metaphor made R draw pure insanity on the chalkboard.

Things started simply enough with a tunnel and a few stick figures. Soon more people were added alongside lines upon lines of levels in the cave. Arrows appeared to show movement in, out, and through the cave. All the while, R kept flipping his voice between faint whispers and loud exclamations. There was no in-between.

In the end, we looked at the board and saw the most glorious mess of a diagram ever conceived.

Remember: Worthy Difficulty

Now, R’s classes had a clear price other than tuition.

He was one of the college’s hardest graders.

One of his favorite tricks was giving someone two grades for an essay. Participation in class and quality of later essays determined which grade shaped your final grade.

Thankfully, this practice opened my eyes to my big problem in those earlier days of college.

My first essay for R earned a B- for analysis and a B+ for style. He said I had great base writing skills and fit well within my chosen craft. My essay’s content just did not provide the level of analysis he expected. I had leaned more toward simple summary of course material rather than explanation of the thoughts behind them.

R was right.

The problems he noticed were my same problems in my earlier courses. I could finally see them.

I was so focused on developing as a writer that I had forgotten to develop as a thinker. Snappy titles, good paragraph lengths, and varied sentence structures were more important to me than constructing a good argument or providing quality evidence for my ideas.

Finally knowing my weaknesses, I went to work improving my next essays. I still had a way to go though, so I only improved enough to earn a B+ in the class.

Still, now I knew my path going forward.

Finishing the Honors Program

My focus was now developing thinking and communicating it in writing.

Connecting quotes to clear explanations and refining arguments took priority over mechanics and style. I made my statements as simple as possible, never saying more than attached quotes would allow.

This strategy earned me far better grades in the Honors Program’s remaining history courses. Granted, no professor was tougher than R, but they did not give easy grades either.

Eventually the time came for my tutorial, my final course in the Honors Program. The choice was clear the moment I saw the semester’s class listings.

R would be teaching a tutorial called The Problem of Socrates. The course was described as a capstone experience uniting everything learned in the Honors Program. Ideas from across history would be examined at one of their earliest known sources.

It was also slightly reassuring to take a third college class on Socrates.

More importantly, R would be tougher than ever before. I could prove if I really had grown since my first class with him.

An Important Lesson

The Problem with Socrates began, and I started well.

R had stepped back in his lectures. He wanted to focus more class time on discussion. Somehow, I actually became one of the main speakers during these discussions.

One time, I even remember R smirked and asked me, “Oh, would you like to teach the class?”

My first essay was still in the B range, but this time, I knew how to better myself. I knew to focus on better communicating my thoughts. My writing style was already good enough.

Finally, I started acing R’s essays. Discussion grades also helped ensure my final course grade was an A. Of course, these grades were not my greatest accomplishment in this class.

During final exams week, I went to R’s office to turn in my third essay and get back my second essay. He told me he was awaiting my last essay because my second one was “beautifully written.”

That comment meant far more to me than the letter on top of the essay.

Now I knew I had bettered myself in college. I did not earn that perfect 4.0, but I would not trade the experience behind my hard-earned 3.95. In the end, the worthy difficulty was worth far more than numbers and letters could ever mean. Grades may have their place, but they are no substitute for challenges and experiences.

The Honors Program taught me how to better myself. It showed me there is always room to grow. This mentality has proven essential in all areas of my life, especially my writing.

Kotcher’s Call to Action

If you liked my content and want to make sure you read all my new blog posts, be sure to like my Facebook page and share it with your friends. I post a link there whenever a new blog post goes live each Friday at 5:00 PM EST.

2 thoughts on “Honoring a Worthy Difficulty”