Welcome to the cKotch.Com blog. I’m Christopher Kotcher, and this is The Written World. Time to explore the worlds which writers have made.

There is Another

Fantasy covers a diverse spread of writing. You’ve got stories in other worlds, you’ve got other worlds invading the real world, and you’ve got the real world invading other worlds.

Many fantasy fanatics may recognize the genre as an evolution of fairy tales. We’ve taken these stories meant to teach morals and created whole worlds out of their conventions.

Furthermore, two names you always hear when talking about the origin of fantasy are C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.

Lewis most famously wrote The Chronicles of Narnia. He wanted to create a fantastical world to communicate his Christian apologetics.

Tolkien, the founder of Middle Earth, needs no introduction. The Lord of the Rings stands as a true achievement across literature, film, and even video games.

These two certainly deserve to be seen as founders of fantasy. They took the fundamental elements of fairy tales and made something new out of them.

How would you react if I told there was a third?

Not only that, what if I told you this third was actually the first of these three? What if I told you he was a man who inspired both Lewis and Tolkien?

This man would be the Scottish author George MacDonald. He was a preacher whose teaching emphasized the universal love of God.

In fact, MacDonald was not only a model to Lewis and Tolkien, he also mentored one young Lewis Carroll and convinced him to publish Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

Take any English fantasy novel you can find from the nineteenth century or early twentieth century. Chances are that book was at least partially inspired by MacDonald’s work.

Today, poor old MacDonald is largely left forgotten. I only even learned of him through reading Lewis and Tolkien. I had found enough similarities between them to wonder if they shared some common inspiration.

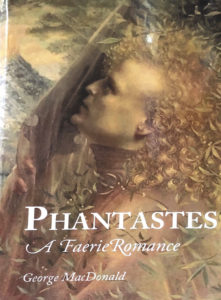

In this past year’s Christmas book haul, I included two works from MacDonald. I’ve come to love both of them, and I’d like to share some thoughts here.

Let’s see if I can get you interested in this forgotten founder of fantasy.

The Golden Key

This would be one of MacDonald’s more traditional fairy tales. The book’s subtitle is even “A Victorian Fairy Tale.”

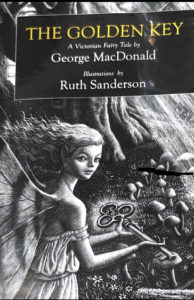

The Golden Key is short. Its nine chapters could easily be covered in thirty pages. Most longer copies feature illustrations of the book’s fairy tale imagery.

My copy’s illustrations come from professional illustrator Ruth Sanderson. Her “Illustrator’s Note” at the end of the book discusses her decades-long love for the story, how she had always dreamed of illustrating the story. I could see that love from the very beginning.

In many ways, this is a typical fairy tale world. The story centers around a single object which holds some mystic purpose that’s never fully explained. The tale begins with a young boy and a young girl who live near the woods.

Then the twists start coming.

For one, this fairy world has a few odd mechanics to it. There are actually hints of worldbuilding.

Key example would be the story’s owl fish.

These creatures start their lives as actual fish. They gain their owl faces and ability to swim through air after being raised by the wise Old Man of the Sea.

The owl fish fly through the forest and lead human travelers to a young lady named Grandmother. She cooks owl fish in a pot and serves them to the human.

Having sacrificed itself to nourish humanity, an owl fish’s soul is revived inside the cooking pot. The soul then manifests itself as a guardian fairy called an aëranth.

So, what happens in the central plot of The Golden Key?

Well, a young boy named Mossy hears about a golden key that rests in the fairy woods. He searches for it and finds it with ease, but he has no idea what to do with it.

At the same time, a young girl named Tangle sneaks away from home and finds her way to Grandmother’s house. When Mossy appears there too, Grandmother sends the pair to find a use for the golden key.

Mossy and Tangle travel through the fairy lands. Time seems to both fade and accelerate for them. They become adults just by walking together through the woods. They spend a lifetime with each other after only a few steps.

Soon, the pair find a series of beautiful shadows coming from the distance. They wonder what forms could possibly produce such shadows and make it their quest to find “The Land from Whence the Shadows Came.”

Through ever more twists and turns, Tangle and Mossy reach the door to “The Land from Whence the Shadows Came.” They use the golden key to open the gateway and find themselves in paradise.

The ending really is unique for a fairy tale. In most, you’d expect the main characters to leave the woods and return home, having learned some major life lesson.

Here, Mossy and Tangle go through the fairy wood. They grow old together there on their journey. Their final destination is a place which seems to be both beyond their home and the fairy world.

In the afterword of my copy, scholar Jane Yolen states that The Golden Key has three traditional readings: a realistic story embellished with fantasy elements, a metaphor of life and death, and a fairy tale filled with religious imagery.

I must confess I tend more toward the religious angle there. A place beyond home and beyond the fairy woods that feels even more like home? That sounds very similar to how I’ve heard many teachers and preachers describe heaven.

Most fairy tales ultimately tell stories about living in this world. MacDonald told one about finding your way to the next world. It fits right in with his preaching on universal love and eternal destiny.

Phantastes

Here we have a MacDonald fairy tale with a few more twists. It has some traditional elements which The Golden Key lacks, but it also diverges in some important ways.

Phantastes stars the young dreamer Anodos. On his twenty-first birthday, he receives a desk from his late father. He is an adult now, and he is called to begin his working life.

However, when Anodos opens the desk, he finds a small statue of a woman. The form of the statue fits his lofty artistic ideals of femininity. He becomes obsessed with it.

The statue then comes to life. She mocks Anodos’ professions, saying she’s old enough to be his grandmother (226 years his senior, in fact).

Mocking Anodos’ idealist philosophies one last time, the statue announces she will soon be sending him on a trip through fairy land. Here the dreamer will learn how to move beyond his ideals.

After a good night’s sleep, Anodos wakes to find his room folding into fairy land. His bed becomes cool grass under a tree’s shade. A small stream appears through the area. Soon enough, the room transforms into a full forest entrance.

Like I said, Phantastes has some twists unseen in The Golden Key. In fact, the stories seem polar opposites at times.

While Mossy and Tangle travel to a land of forms and ideals, Anodos journeys through fairy land to learn the flaws in his own ideals of heroism and romance.

Perhaps the difference in these morals comes in the hearts of the characters.

Mossy and Tangle grow but keep the hearts of children. They see true ideals in fairy land’s shadows and aspire to reach them. They want to live in the world of these true ideals.

Anodos, a proud twenty-something, assumes his lofty ideals are perfect. He believes they will guide him through his adult life without any issue. He expects everyone else to live according to his own assumptions.

Getting back to Phantastes specifically, Anodos runs into plenty of women who defy his ideals.

He falls for a marble lady. She leads him into a cave and tries to feed him to an evil forest spirit. The hopeless romantic sings another statue to life. He touches her once, and she runs away screaming.

Anodos finds helpful women in a hard-working village mother and an elderly guide. The mother shares secrets of fairy land’s more dangerous inhabitants. To help him work through his past, the elderly guide leads Anodos through four doors of memories.

Anodos’ only genuine romance comes with the spirit of a beech-tree. She longs to be human one day, and Anodos pleases her by praising her beauty. In gratitude, she sings for him.

The misguided idealist learns of romance in other ways as well. At one point, he stumbles on a grand fairy palace. Here he finds a library that quite literally sucks you into its books.

Anodos becomes a character named Cosmo. He gets to live Cosmo’s grand romantic adventure of freeing a princess from a cursed mirror.

Thing is, the story defies Anodos’ ideals of love. As Cosmo, Anodos doesn’t get to live a grand life of luxury with a doting princess wife. He has to sacrifice himself. He destroys the mirror and takes her curse to free her. Anodos’ final moments in the character of Cosmo involve dying in the princess’s arms.

Many similar scenes occur in Phantastes. Anodos becomes an accidental giant slayer. He learns to occasionally forego romance in favor of friendship. He serves as a squire to a knight.

Phantastes truly is a work of art. In fact, this book is directly responsible for sparking the imagination of MacDonald’s fellow founder of fantasy, C.S. Lewis.

According to his autobiography Surprised by Joy, Phantastes was a major element in ending a major dry period in Lewis’ life. It opened him to a whole new world.

“The woodland journeyings in that story, the ghostly enemies, the ladies both good and evil, were close enough to habitual imagery to lure me on without the perception of change. It is as if I were carried sleeping across the frontier, or as if I had died in the old country and could never remember how I came to live in the new.” (Chapter 11: Check)

Plenty More

There are plenty more books by George MacDonald. He’s got quite the catalog.

Unfortunately, I’ve only read two of his works. So, I won’t be delving too deeply into stories of vengeful goblins and tales of princesses cursed to live without gravity.

On the scale between fairy tale and fantasy, MacDonald certainly leans more toward fairy tale. However, he began manipulating elements in ways which allowed fellow founders Lewis and Tolkien to craft a totally new genre.

Fairy woods and fairy lands could be established worlds rather than simple diversions to learn a lesson or two. Characters could remain within fantastical realms instead of returning to more realistic worlds.

Perhaps the main reason MacDonald is so often forgotten lies in how gradual his changes were.

Far too often, genius can be misunderstood as needing to come from some radical break from prior traditions and beliefs. Without MacDonald, Lewis and Tolkien provide this kind of clear break between fairy tales and fantasy.

According to this view, Lewis and Tolkien appear far brighter if MacDonald is left in the darkness.

However, genius is often found in those who can change little details. Most geniuses actually take something old and find ways to improve and make it new. They find new forms to carry out long-standing ideals.

According to that view, one can give MacDonald his due appreciation in addition to Lewis and Tolkien.

Discussion Time!

I always love finding new writers to follow. MacDonald’s earned more than a few spots on my future reading list.

What do you think of MacDonald? Did you know about him before, or was this your first time hearing about him? Do you think he deserves to be more well-known?

Kotcher’s Call to Action

If you like my content and wish to see more, you could check out my books Five Strange Stories and Good Stuff: 50 Poems from Youth on Amazon. They are enrolled in the Kindle Matchbook program, so anyone who buys the paperbacks can also get the eBooks for free.

Finally, be sure to like my Facebook page and share it with your friends. I post a link there whenever a new blog post goes live each Friday at 5:00 PM EST.

1 thought on “The Written World #1: The Forgotten Founder of Fantasy”