Welcome to the cKotch.Com blog. I’m Christopher Kotcher, and this is The Written World. Time to explore the worlds which writers have made.

One Fine Day in English Class

My first major reading list came from my old high school’s AP World Literature class.

Our teacher walked into class one fine day. Rather than approach the podium, he walked to a chalkboard off to the side of the room and started writing.

We all thought he was going crazy. He didn’t even bother to say what we were doing. So, we just leaned back in our seats and relaxed, only taking a few glances at the board.

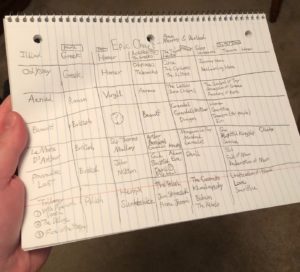

A chart began to appear. Books, cultures, characters, and themes started filling it out.

We recognized a few titles.

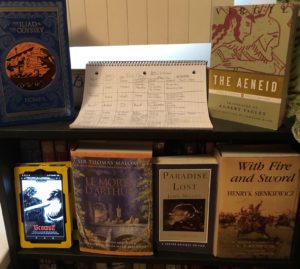

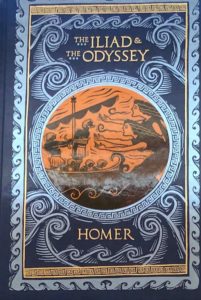

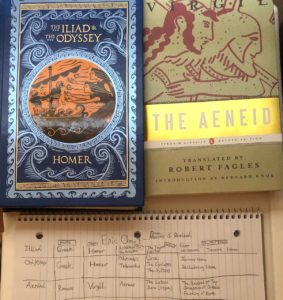

Beowulf was one of our Honors Freshmen English books. The Iliad and The Odyssey came up in pretty much every history class which covered the Greeks.

A few weird ones came up. What in the world were The Aeneid, Le Morte d Arthur, or With Fire and Sword?

Paradise Lost raised a few eyebrows. The devil was listed as both a hero and a villain for that one. Of course, the hero column did see a circled question mark by his name.

When our teacher set down his chalk, he explained this Epic Chart would be the focus of our next marking period.

The chart detailed seven sweeping tales of heroism that informed the values of whole civilizations.

Heroes in each epic represented growth in a culture’s values. They were those who became ideals through either founding or continuing a culture.

Our teacher chose these seven epics to chart the growth of Western Civilization. This focus was the most natural spot for us. It was the literary culture which led most directly to our own.

Unfortunately, our class time was limited, and other classes existed. Our class could only grasp at the works of the Epic Chart through excerpts and packets.

Still, that was enough to light a fire in me. Within a year, I would come to own most works of the Epic Chart. I would read all that I owned within a few months afterwards.

Today and next week, I wish to glimpse into my journey following the Epic Chart. I want to show you what reading these pieces together and comparing them to each other did for me.

While I initially hoped this all could be handled in a single post, I now believe the subject will best be tackled across three posts.

For now, we will only cover the first three works of the Epic Chart. They are similar enough where their general themes can be pulled out and discussed.

Next week, we’ll see how the next three works of the Epic Chart proceed from the prior three, and in two weeks, we’ll cover the final entry on the chart and discuss the general takeaway.

So, without further ado, let’s get to the Greeks.

Homer’s Trojan War

The Trojan War was the backbone of Greek mythology. It was the classic Avengers-level event which brought together all the greatest heroes of its day.

The war began when the proud Trojan prince Paris settled a divine dispute. Three goddesses were quibbling over who deserved a golden apple with a dangerous message.

“For the Most Beautiful.”

Paris declared the goddess Aphrodite the winner. She had bribed him with the promise of the world’s most beautiful woman to be his wife.

Unfortunately, Lady Helen was already married to the Spartan king Menelaus. So, when Aphrodite snagged Helen, Menelaus grabbed his brother Agamemnon and went to war.

Additional Greek heroes then joined the fray. They would fight to gain glory and plunder treasure.

You see, this wasn’t really the most moral of wars. The Ancient Greeks were warriors. Their greatest goals in life were to be great conquerors and powerful rulers.

In fact, the Ancient Greek perspective led them to recognize many Trojan warriors as heroes. This was possible because being a hero then simply meant being able to dominate others.

Within this culture, the war’s two standout tales were The Iliad and The Odyssey, both told by the blind poet Homer.

The first tale tells of the rage of Achilles, prince of the Myrmidons, greatest of all heroes. He rages right off the battlefield when Agamemnon takes his girl Briseis.

(Yeah, there’s no skirting around this one. Ancient Greece has a bad habit of counting women as spoils of war. Agamemnon could seize her because any spoil in his army technically belonged to him.)

The furious Achilles wishes for Agamemnon to suffer and for Greeks to die so he can save the day and be appreciated. He then proceeds to pray to his sea nymph mother Thetis to make it so.

Unfortunately, these fulfilled prayers lay claim to Achilles’ dear comrade Patroclus. The young soldier dies at the hands of the next Trojan king, Hector.

Achilles then returns to the battlefield to reclaim Patroclus’ body, kill Hector, and drag Hector’s body underneath his chariot before throwing it to the dogs.

A few nights later, Troy’s King Priam sneaks into the Greek camp and begs for his son’s body. Hector’s funeral closes the tale.

The Odyssey picks up after the war. Here, the crafty tactician Odysseus struggles through ten years of hardship at sea to return to his island home of Ithaca.

Meanwhile, Odysseus’ son Telemachus searches for his father. The boy wishes to save his home from the wicked suitors hounding his mother Penelope and ravaging everything they touch.

In the end, Odysseus returns and reclaims his home. He and his son even slaughter all the suitors.

The people of Ithaca then seek revenge on Odysseus’ family for the suitors since many of them were proud people of the island. A second massacre is prevented only when the goddess Athena intervenes and establishes a truce.

Again, Ancient Greek myths weren’t really modern morality tales. Sure, appeasing the gods was stressed but that was mainly to avoid a good smiting.

Heroes were those who could dominate others. The more power you had, the greater you were. You were only lesser than the gods because they had the power to dominate you if you tried.

The Ancient Greek morality was clear. Be the best you can be. Destroy anyone who stands in your way. Rule as a king.

This tradition would empower the Ancient Greeks to be great conquerors. It even became a tradition which future conquerors sought to emulate.

Successor of Homer, Successor of Troy

Rome was one of the world’s greatest historical powers. Their empire grasped three continents and lasted far longer than most countries living today.

Naturally, such a power would want a nice mythology to support itself. They may even want to link themselves to a prior world power to emphasize their own strength.

This link would come through the pastoral poet Virgil and his great poem, The Aeneid.

The story picks up as the Trojan War ends.

Paris kills Achilles with a sneaky arrow launched from the Trojan wall. Odysseus crafts the Trojan horse as a false peace offering only for Greek soldiers hiding in it to begin the brutal Sacking of Troy.

The Trojan heroes fall in battle. Achilles’ son Neoptolemus slays the Trojan royal family, including Hector’s infant son. Helen reconciles with Menelaus moments before he turns his rage on her.

Only one Trojan hero remains, Aeneas, the Son of Venus (Roman name for Aphrodite). Aeneas follows his mother’s guidance and escapes the burning city with his elderly father, young son, and a small band of soldiers.

They are all that remain of the Greeks’ greatest rival.

Aeneas travels to the distant city of Carthage for refuge. There, he marries the queen and buries his father.

However, remaining in Carthage is not the will of the gods. Aeneas receives a vision, telling him to go to Italy and build a great city which will come to rule the world.

(Fun Fact: Carthage was one of Rome’s greatest rivals. This poem actually seeks to explain the conflict by saying the spurned queen prophesied Aeneas’ people would be doomed to future war with her people.)

Docking in Italy, Aeneas leads his small force to the ancient city Latium. He wages war to unify the peninsula and its people under his new city, Rome.

The Aeneid did not seek to change the values of the Ancient Greeks. Again, this epic represents one conqueror declaring itself the successor to a prior conqueror.

While Rome linking itself to the failing Trojans rather than the victorious Greeks may seem strange, the connection actually makes more sense than you may first realize.

Vengeance was a law within the ancient world. You take from others what they take from you. If you cannot attain vengeance yourself, it becomes your family’s duty to do so on your behalf.

This is why Neoptolemus eliminated the Trojan royal family. He knew leaving any of them alive would doom him to facing them again and, possibly, falling at their hands.

After all, Neoptolemus slaughtered them only because they slaughtered his father. His father returned to slaughtering Trojans only because Hector slaughtered Patroclus.

By linking itself to Troy, Rome worked on behalf of Troy to claim the power which Ancient Greece once took from the city. Rome could succeed Ancient Greece according to the law of vengeance.

From there, it’s all the same idea. Be the best you can be. Destroy anyone who stands in your way. Rule as a king.

The Conquerors’ Old Ideals

Of course, these ideas of conquest and domination aren’t the primary values today.

Many horrors were committed in these first three epics. We can only quiver and shake at them now because the things we value have changed so greatly from the time these tales were written.

However, this leads us to some important questions.

Why did things change? Why do conquest and domination no longer seem to be the principle values within our culture?

Sure, there may be some who come to value their power over others as a supreme good, but they are not the norm anymore. Generally, they are detested and resented.

My answers to these questions will come next week when we examine the next four epics of the Epic Chart. We will see how they represent a major shift leading from the first three epics into our modern day.

Discussion Time!

Well, I already posed some questions in that last section there.

Why did our values change since the first three epics of the Epic Chart? Why do conquest and domination no longer seem to be the principle values within our culture?

Let’s hear what your answers may be after reading this post. Then, next week, you can compare your answers to mine.

Kotcher’s Call to Action

If you like my content and wish to see more, you could check out my books Five Strange Stories and Good Stuff: 50 Poems from Youth on Amazon. They are enrolled in the Kindle Matchbook program, so anyone who buys the paperbacks can also get the eBooks for free.

Finally, be sure to like my Facebook page and share it with your friends. I post a link there whenever a new blog post goes live each Friday at 5:00 PM EST.

Loved the post Chris! It seems to me that humans have these tendencies in them to dominate and seek vengeance for wrongs perceived and real in every generation, but whereas in the ancient times the culture idolized them in its heroes and works, there’s a new law which shows these tendencies to be empty and ultimately destructive. The law of charity exemplified by Christ on Calvary.

Good observations. You’re going to love Part 2!