Welcome to the cKotch.Com blog. I’m Christopher Kotcher, and this is The Written World. Time to explore the worlds which writers have made.

Conclusion to the Epic Chart

This week concludes my three-part series on the seven entries of the Epic Chart from my old AP World Literature class.

Part 1 centered around Greco-Roman epics. We explored a world of conquerors whose primary motivations were domination and vengeance.

Part 2 discussed three epics written as culture adjusted to fit new Christian values of sacrifice and service.

Today, the series concludes.

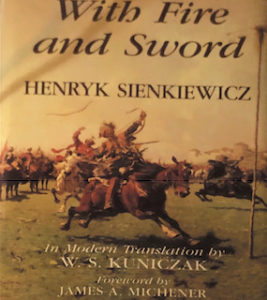

One entry remains on the Epic Chart, Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz’s Trilogy.

The Trilogy of Sienkiewicz contains three titanic historical fiction novels. They tell tales of three seventeenth-century Polish wars in the classical epic style.

I must admit here I’ve only read the first book of the Trilogy, With Fire and Sword. English translations of the rest of the series have unfortunately proven hard to come by.

Still, the story of the first book alone is a grand tale which deserves mention here. It’s actually a pretty good capstone to everything we’ve been talking about regarding epics.

Sienkiewicz combines all elements of epics with the history of his home. He did so in a time when Poland had been divided by conquerors and absorbed into Russia.

The author sought to make an epic to remind his people of their history and to unify them according to their common traditions and values.

The tale tells of the fictional Yan Skhetuski, lieutenant knight of the ferocious yet devout Prince Yeremi. Even in history, Yeremi did well to earn his nickname of Yerema the Devil.

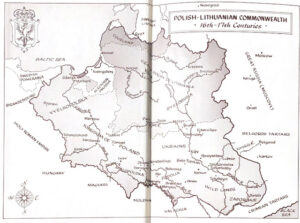

Skhetuski finds himself ensnared in an uprising within his home, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In fighting for unity, he finds love, loses friends, and becomes an ideal knight.

The Historical

We begin with the historical element of this historical fiction epic. Sienkiewicz provides some intriguing twists in how he inserts his story into the drama of the Cossack Uprising.

You see, the Cossacks were a people from the eastern grasslands known as the Steppe. They demanded liberation from the rule of commonwealth nobility.

Of course, this liberation would mean fracturing the unity of the commonwealth. The great kingdom would be weakened in a world filled with enemies.

The revolt began under Cossack leader Hymelnitzki, head of the Zaprozhian Host military force beyond the Dnipro River.

Thanks to a chance encounter, Skhetuski finds his fate linked to this powerful enemy.

While returning home from a mission in the Steppe, Skhetuski discovers a man being ambushed by four horseback raiders. The knight saves the man and gives him a horse to ride to safety.

The man then reveals himself to be Hymelnitzki himself. Skhetuski does not know the name until he returns to Prince Yeremi and hears that the rescued man has begun his rebellion.

Naturally, the Polish knight feels responsible for saving the man who now threatens to divide his country. Ready for redemption, Skhetuski departs to strike his foe’s base at the Dnipro River.

The bloody battle proves especially grueling when Hmyelnitzki’s forces welcome nomadic invaders known as Tartars. The uprising forces override the Polish troops and capture Skhetuski.

However, Hymelnitzki recognizes the knight and orders him captured rather than killed. The rebel then takes the knight prisoner and personally transports him home while on the war path.

An impressive clash of ideals rages here. Sienkiewicz proves a master in providing dialogue as fierce and brutal as his battles.

[Hymelnitzki] “I don’t want war with Commonwealth! She is my own mother!”

[Skhetuski] “But you are holding a knife to her throat.”

“I’ve got to free the Cossacks from your chains!”

“To put a Tartar rope around their necks…” (155)

“Shut your mouth, you screech-owl!” Hymelnitzki howled, enraged, and leaped to his feet. “Who made you my conscience?”

“You’ll choke on your own country’s blood,” Pan Yan [Skhetuski] cried out fiercely. “You’ll drown it in tears! The only thing that’s waiting for you in the end is judgment and death!”

“Silence!” And Hmyelnitzki’s knife glittered once more at Skhetuski’s throat.

“Do it!” Skhetuski grated out. “Begin it with me!” (155)

Both men seek to honor their home. One preserves its traditions and unity above all else. One seeks to replace the rule of distant tyrants with his own rule.

Both are the heroes of their own stories. Both owe each other their life. Both will do great things in this war.

As in history, Hymelnitzki gets to create and lead his own Cossack state.

In this story, even if Skhetuski can’t preserve the unity of his home, he is still able to protect the people he serves. He rallies the forces of the Commonwealth’s ruler King Casimir to ensure the survival of Yeremi’s domain.

In a way, we see a unique twist on an old tradition here. Like with the Greeks, we see heroes against heroes.

The key difference here is what makes them heroes. They are heroes because they are champions of their ideals, not because they are conquerors. They fight only because their ideals can’t be harmonized.

True Friends

Skhetuski is not the only Polish hero within this work.

The first two enter the picture once Skhetuski leaves the Steppe.

In a tavern, Yeremi’s proud knight meets the crafty old Zagloba, a true knight of the world.

Zagloba has a tale for anyone willing to listen, though many would call him a rambler. He has travelled distant lands, devised numerous schemes, and survived capture by many foes.

Physically, the old knight is most distinguished by his blind eye. According to him, the eye’s silver film comes not from age, but from some torture he once suffered at the hand of an enemy torturer.

With a laugh Zagloba introduces, Skhetuski to a young recruit for Yeremi’s service.

The lanky Lithuanian with a mighty sword, Longinus Podbipyenta towers over all men. With one hand he can wield his family claymore Cowlsnatcher. Most can’t even hold it with two.

He fights to fulfill a family vow to behead three enemy soldiers with one swing of their ancestral sword.

Additional heroes enter as Skhetuski travels to Yeremi with Longinus. He reunites with his young comrades, the greedy squire Zjendjan and the fierce swordsman Michal Volodyovski.

Zagloba takes some to come around to protecting the Commonwealth, but all these heroes form a deep bond. Together, they strive to represent the best their country has to offer.

The ideals of the Christianized epics are seen in follow display in all of them, particularly in Longinus.

In his final battle, Longinus gives everything in a desperate attempt to gain support from the new Polish King Casimir to support Yeremi’s troops.

The towering knight makes one last stand against a tree. He fights hordes of men, swatting them away with mighty Cowlsnatcher. He stands his ground even as they bind him with ropes.

Through it all, Longinus recites prayers to Mary, the Mother of Jesus, to strengthen his resolve and hold true to his ideals until the bitter end.

The new knight’s honor is especially seen when his body is recovered the next day. His funeral sermon ends with the declaration:

“Goodbye to you then, our dear friend and brother! You didn’t reach our earthly king, that’s true, but you brought our tears and hunger and misery and word of our suffering to the King of Heaven! That’s a much more certain source of our succor and rescue! But you, yourself, won’t be coming back to us again. And that’s why we weep over your body.” (1066)

No Truer Romance

Enfolded in the history, Sienkiewicz provides an additional plot. Skhetuski’s friends fight for the freedom and safety of Skhetuski’s beloved.

While meeting his fellow heroes, Skhetuski also meets his love interest. She will become the center of the epic’s other central conflict.

Princess Helen comes from a small yet respected noble house. Unfortunately, her aunt has watched it since the princess’s youth and keeps much of the princess’s inheritance for herself.

This aunt has adopted a fiery Cossack soldier named Bohun. The man believes Helen belongs to him, and the aunt would have things no other way.

Then Skhetuski and Helen fall in love. The knight finds it his duty to protect her and help her secure her inheritance from her aunt’s schemes. The aunt happily agrees to the new deal.

After all, what good is getting your niece’s inheritance through marrying her to your adopted son when you can be in the good graces of a powerful prince and his reputable knights.

Bohun does not take news well.

After Skhetuski leaves, Bohun burns Helen’s ancestral home, slays most of his adopted family, kidnaps Helen, and defects to Hymelnitzki’s army.

What we have here is a clear callback to the Trojan War. Although, here, Sienkiewciz places Skhetuski in the right for leading Helen away from an unwanted engagement and future abuse.

Essentially, Bohun manifests the same possessive rage as Menelaus of Sparta, but that rage is now exposed as something negative and corruptive.

The news tortures Skhetuski. He yearns to free his beloved, but he is honor-bound to remain with his prince’s army during the uprsing.

This would be Skhetuski’s friends, the other heroes, find some extra time in the sun.

Hymelnitzki’s first mission for Bohun places him as a courier, delivering messages between uprising forces and Yeremi’s army. To represent the Polish, Zagloba takes part in these missions.

Initially, Zagloba respects Bohun for his power. Then the old knight sees Helen held captive in the camp. They start talking, and he comes to form something of a fatherly bond with her.

When Zagloba learns Helen is engaged to Skhetuski, the old knight knows he is backing the wrong corner of the love triangle. He helps the princess escape.

From there, everyone gets a chance to shine.

Longinus leads the charge in battle against Bohun’s forces. Zjendjan collects information no one else could find, and Volodyovski slices Bohun to ribbons in two duels.

Those duels are particularly brutal. Bohun’s only even able to survive the first one thanks to the help of a witch.

Helen even gets her fair chances to shine.

When with Zagloba, the princess must disguise herself as a young soldier. She does everything she can to keep the bit going until she can escape the warzone.

When Bohun kidnaps Helen a second time, she defies him at every turn. She knows he won’t dare hurt his prize and actively uses that knowledge against him.

Everything Comes Together

When With Fire and Sword comes to a close, Hymelnitzki gets his Cossack State, Skhetuski marries Helen, and the knights gather together to remember fallen heroes.

As I said, Sienkiewicz wrote three epic historical novels on Poland’s major seventeenth-century conflicts.

The Deluge chronicles the Commonwealth’s war with Sweden. Fire and the Steppe features war with the Ottoman Empire.

Perhaps one day I will read those other works, but for now, With Fire and Sword remains a good conclusion to our coverage of the Epic Chart.

The book combines many things into a 1000-page behemoth. I’ve only really barely scratched the surface here.

Still, I hope to have shown how the developments in Epics led to this point. This is a work where old ideas are revisited and new ideals are unified with them. There is truly nothing else like it on the chart.

Discussion Time!

I hope you’ve enjoyed our three-week dive into epics. I really can’t believe I initially thought this could all be handled in one week.

Still, it feels good to finish this series. It was quite the heavy workload. It’s been years since I’ve ready many of these works, and I’ve done my best to try grasping them again.

What do you think of the conclusions I’ve offered on each of the epics? Are there any you now wish to read thanks to these posts?

Kotcher’s Call to Action

If you like my content and wish to see more, you could check out my books Five Strange Stories and Good Stuff: 50 Poems from Youth on Amazon. They are enrolled in the Kindle Matchbook program, so anyone who buys the paperbacks can also get the eBooks for free.

Finally, be sure to like my Facebook page and share it with your friends. I post a link there whenever a new blog post goes live each Friday at 5:00 PM EST.